By Michael Phillips | Virginia Bay News / Father & Co.

Across Tennessee, a quiet procedural change is spreading county by county — one that supporters say could save lives, and critics warn could erode due process if left unchecked.

The change does not create a new gun law. It does not expand who is prohibited from owning firearms. Instead, it tightens paperwork around an existing requirement: when a person subject to a domestic violence conviction or protection order is barred from possessing firearms, any transfer of those firearms to a third party must now be documented in detail.

The reform began in Scott County, East Tennessee, and has since been adopted by at least nine counties, including Davidson (Nashville) and Shelby (Memphis). Judges in those jurisdictions now require sworn affidavits identifying the individual receiving the firearm, including name, address, and a signed acknowledgment that the weapon is in their custody.

Supporters argue this closes a dangerous loophole. Critics argue it exposes deeper tensions between victim safety, enforcement gaps, and constitutional safeguards.

A Procedural Fix, Not a New Ban

Under federal law — including the Lautenberg Amendment — individuals convicted of certain domestic violence offenses, or subject to qualifying protection orders, are prohibited from possessing firearms. Tennessee law mirrors that framework. The controversy is not over prohibition, but enforcement.

Previously, Tennessee’s standard relinquishment form allowed a respondent to state that firearms had been transferred to a third party without identifying who that party was. Courts had no reliable way to verify compliance.

Judges in Scott County changed that. Other counties followed.

Shelby County Criminal Court Judge Greg Gilbert described the fix as “shockingly simple,” saying it made compliance more serious without rewriting the law.

Victim advocates point to grim statistics: Tennessee consistently ranks among states with the highest rates of women killed by intimate partners, often with firearms. Investigative reporting by WPLN and ProPublica found that roughly one in four victims of domestic violence gun homicides in the state were killed by someone who was legally prohibited from having a gun.

Why Statewide Action Stalled

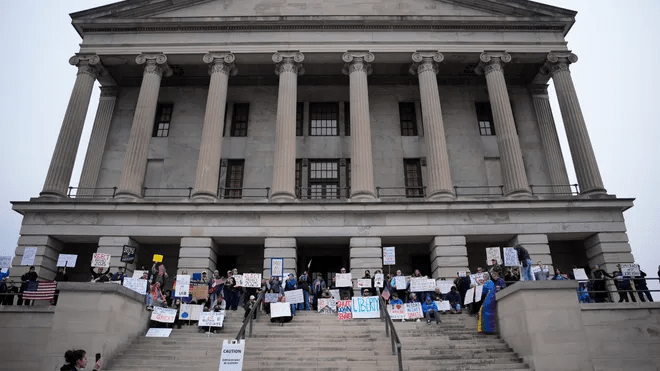

A 2025 bill to standardize the enhanced form statewide failed to advance, drawing opposition from groups including the National Rifle Association and the Tennessee Firearms Association. The bill is expected to resurface in 2026.

Notably, the sponsors were Republicans, and at least one was an NRA member — underscoring that opposition was less about party politics than principle.

The Concerns Often Left Out

Much of the public coverage has framed the issue as a binary conflict: victim safety versus gun rights. That framing misses legitimate center-right concerns that deserve scrutiny:

Due Process in Temporary Orders

Many protection orders are issued ex parte — without the respondent present — and are later dismissed or expire. Critics argue that adding layers of enforcement tied to temporary allegations risks permanent consequences without adjudication.

Privacy for Law-Abiding Third Parties

Friends or relatives temporarily holding firearms may now be required to disclose personal identifying information to courts, raising concerns about privacy, data retention, and unintended exposure.

Enforcement vs. Expansion

Gun rights advocates argue the problem is not the lack of rules, but the failure to enforce existing ones — a systemic issue that paperwork alone cannot fix.

Slippery Slope Anxiety

Even administrative changes are viewed warily in a state with strong Second Amendment protections. Critics fear incremental normalization of gun-tracking mechanisms that could expand over time.

These concerns do not negate the reality of domestic violence. They reflect skepticism about whether procedural tightening addresses root failures — or simply creates new ones.

A Narrow Fix With Broad Implications

What makes Tennessee’s situation notable is not the form itself, but how it is spreading: county by county, judge by judge, in the absence of statewide consensus.

This grassroots approach allows local courts to respond to documented failures without legislative overreach. It also creates a patchwork system where enforcement varies by geography — raising equal protection questions of its own.

For parents navigating family court — a central focus of Father & Co. — the issue hits close to home. Protective orders can be lifesaving tools. They can also be misused, mishandled, or imposed without adequate safeguards. Any reform touching firearms, custody, or parental rights must balance urgency with restraint.

The Question Tennessee Has Yet to Answer

Tennessee’s counties are trying to fix a real problem with a minimal tool. Whether that tool remains narrow — or becomes a stepping stone to broader restrictions — will determine whether it earns durable public trust.

As the legislature revisits the issue in 2026, the debate should expand beyond slogans and statistics. Victim safety and constitutional rights are not mutually exclusive. But preserving both requires transparency, proportionality, and respect for due process — not just better forms.

Support Independent Journalism

Virginia Bay News is part of the Bay News Media Network — a growing group of independent, reader-supported newsrooms covering government accountability, courts, public safety, and institutional failures across the country.

Support independent journalism that isn’t funded by political parties, corporations, or government agencies

Submit tips or documents securely — if you see something wrong, we want to know

Independent reporting only works when readers stay engaged. Your attention, tips, and support help keep these stories alive.